I've been doing a bit of infrared photography lately, and it got me thinking of how very different it is to standard photography. Okay, it's not the complete opposite, the same compositional guidelines still apply. But in other ways you need to have quite a different mindset.

Thinking particularly of standard landscape photography, the best light is around sunset or sunrise. The light has a beautiful warm golden colour. The low angle of the sun means the light rakes across the landscape, revealing texture. And even after the sun has set, or before it has risen, you can get wonderful purple, pink, or orange hues on clouds and the sky itself.

Winter is often the best time for traditional photography, because the sun is low in the sky for much of the day. Whereas daytime during the summer is pretty awful due to the harsh light from the overhead sun.

With infrared photography however, we don't see any of those colours. Typically we're shooting black and white, or for a false colour image. Colours during the middle of the day are much the same as those at sunset.

The low angle of the sun creates great problems when photographing in infrared. While it will depend partly on the sensor / lens / filter combination you're using, lens flare is much more of a problem when photographing in infrared than it is in visible light. With the sun low in the sky and using a wide-angle focal length, getting the shot you want without including the sun in the frame can be quite tricky.

Shooting into the sun is a technique I and many other photographers enjoy using, whether it be for landscape or portrait. The sun can create a very nice rim light effect when used in this way. But for IR photography you'll likely just get a mass of lens flare.

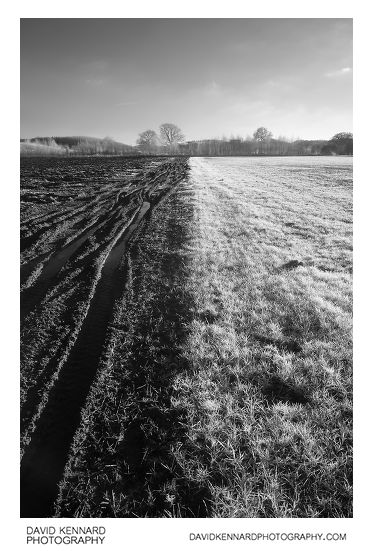

So, what about if we instead decide to shoot in the opposite direction of the sun? Unfortunately, this is not that great either. Finding a composition that does not include your long shadow (caused by the low sun) can be very tricky.

For the image below I had to very carefully position myself to try and keep my shadow within the shadow of the tree trunk, so my shadow would be concealed.

Basically, shooting midday in the summer is typically the best time for infrared photography. Our own shadow will be very short, so we don't have to worry much about it getting in the image. The sun is high in the sky so we don't have to worry about what direction we're shooting in, as it won't be in the frame.

We have strong harsh light, but this is great for infrared photography. Soft light can give an image that is extremely flat for IR photography. I am not sure about the technicalities, but it certainly seems to me that shadows appear brighter in comparison to lit areas in IR photography than they do in standard photography.

The summer is also much better for creating strong contrasts between IR reflecting plants (such as trees) and less reflective items (such as the sky or roads). In winter most trees have lost their IR reflecting leaves, and other plants also have less IR reflecting chlorophyll, meaning they are not as bright as they are in summer.

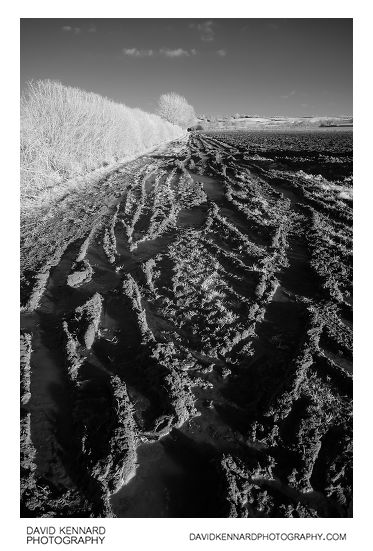

On the same lines, we need to think about how the scene before us will translate to IR. Items that are bright can become dark, and items that are dark can become bright.

For the image below, the partially melted ice in the wheel tracks was quite bright, while the mud was quite dark. In infrared we see the opposite - the mud is much brighter than the wet ice.

All in all, I think we can say that really, this 'oppositeness' is a good thing. We can exploit the softer, warmer light of winter and sunset / sunrise in the summer for standard photography. While the harsh midday light is perfect for infrared photography. We can shoot all day, changing our technique (which includes the spectrum of light we photograph) as the lighting conditions demand.

Still, there is something in me that likes to do the opposite of conventional wisdom. So don't be too surprised if I'm photographing in IR during the winter and then switching to standard photography during the summer!

I agree totally. I’m not that great in the visible light spectrum but in infrared…. I bloom 🙂

Currently just upgraded my camera and now have a hotspot that – if I cannot work out some good reliable ways to remove – will mean junking an AUD$2000 camera…. sigh.

Normally the hotspot is dependent on the lens. If you get the same hotspot with all lenses (or it’s a camera without a removable lens), you could try cornerfix or creating a Raw conversion preset / Photoshop action that you run on all your images to remove the hotspot.